A Story from the North

by Kevin Dyer

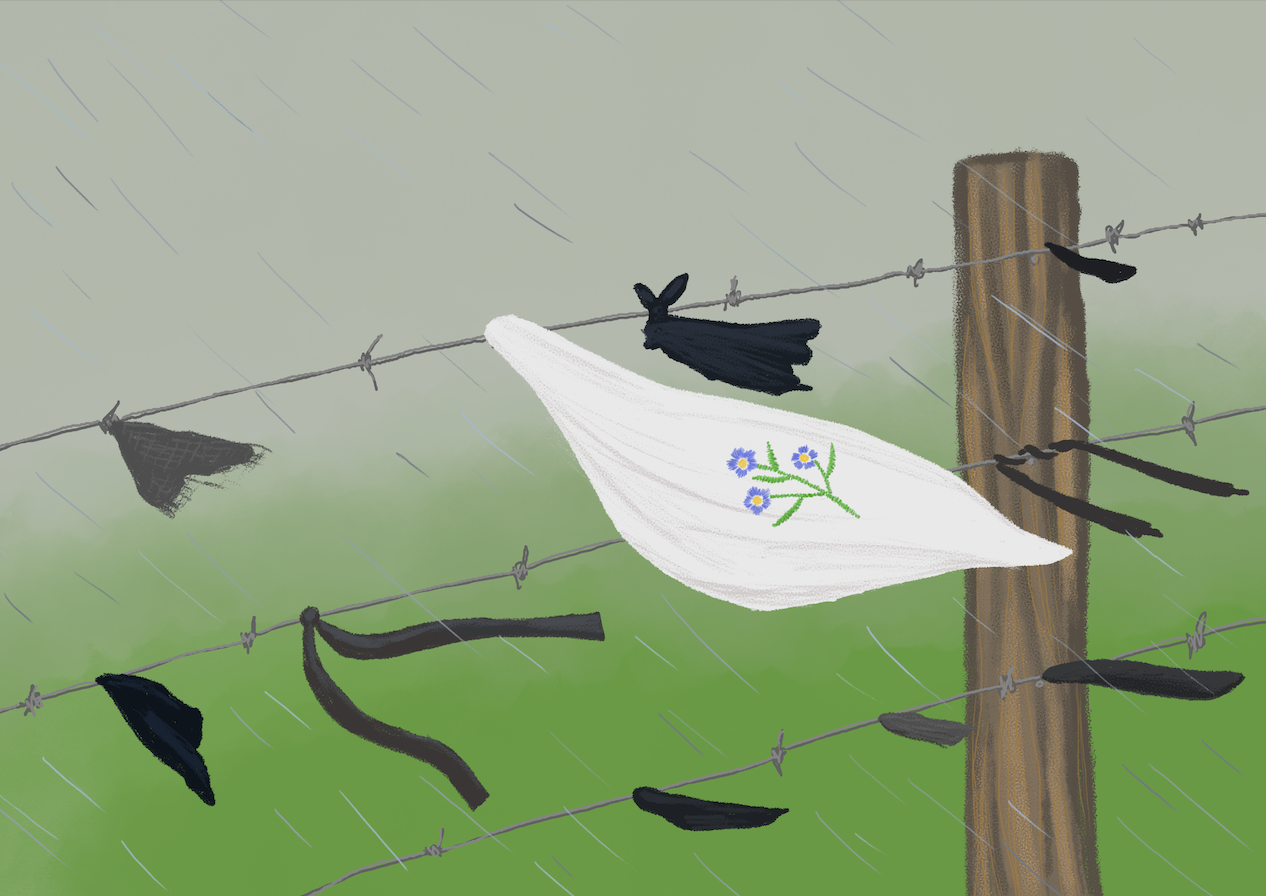

Mynydd Eithinen is the Mountain of Spikes. For thousands of years people have left their marks here. Ditches and dykes, circles of earth, mounds filled with bones and jewellery. It is known, too, they scrambled up here in all weathers and left objects or rags of clothing as sacrifices. Since the beginning of the Chapel movement, however, when paganism was pushed into the corners and people sat in rows in oblong buildings, it is no longer animal furs or brooches made of feathers. Now this is where people come to hang their old funeral weeds. People rip shreds off their shawls or black arm bands, or a button from their black cardigan, and then hang them on a pike or a gorse bush or a barbed wire fence. The scraps of rags rot and perish. It is believed that when they are gone, so is the pain.

Awel heard this old story years ago from her Uncle Dafydd and thought it nonsense – just the stuff that people say when the conversation in the pub dries up. But it was two years now since she’d lost Caitlyn, and the death of a child is the worst of things.

She’d taken time off work, but the rattling round her flat was driving her crazy. She’d found, down the side of the sofa, a piece of Lego and held it until her knuckles went white; she’d woken up in the night and sat on the rug by the side of Caitlyn’s bed; she’d pushed her face into the little wardrobe and breathed in the smell of her gone girl.

She didn’t phone the man who was Caitlyn’s father – he never knew Awel was pregnant, never knew a baby was conceived, so what good would it be telling him she was ill. But carrying it all on your own is a heavy weight.

Her Mum had been great. She’d bring round a carrier bag of broad beans and sit there in the kitchen podding them and talking about nothing in particular. Sometimes she’d tell her daughter that things would get better and time heals, but the young mum, who was a mum no more didn’t want to hear any of that.

She’d gone out with mates, but always ended up coming home early. She’d tried therapy but sat there saying nothing. Because what is there to say.

It was the anniversary. Today was the second year to the day of the funeral.

Awel woke at four; the picture in her head was the tiny coffin of a child

Awel put on her face, the radio blasting loud. She couldn’t stomach breakfast, but she was determined to beat the day. A nice lad, Gareth in accounts, had said they could do lunch today.

But she got to the door and her legs buckled. She fell, dropping her bag, everything spilling out. She also whacked her elbow on the little table where she kept her keys, but she didn’t notice that.

Ping ping ping. She lay on her back and read the messages. Dozens of people, friends, mum of course, all wishing her well and putting on more kisses than usual. She knew what the subtext was: ‘Be brave.’

But she couldn’t be brave anymore. She was broken. She looked at the things that spilled out of her bag… lipstick, chewing gum, tissues, emergency tampon, two pens, her purse, a handkerchief. A proper cotton handkerchief.

Her gran had given her this on funeral day. It had a little embroidered flower on it. A tiny, blue forget-me-not.

She laughed. A dry scoff of a laugh.

Her nose was running, her eyes reddening at the rims.

She texted Gareth, told him she couldn’t make lunch.

She texted her line manager, said she’d got a migraine.

She texted her mum told her she felt shit, but didn’t send it.

‘Come on you bastard,’ she said to the hankie.

She drove to Clwyd Gate, parked by the old motel, locked the car door and walked away. She crossed the road, went down the track, to the stile, up the steep field. The grass was short, smooth, and a buzzard was mewling overhead. Awel didn’t hear it, just her own heartbeat and her rapid breaths.

She got to the highest place. Mynydd Eithinen. She thought it was just a story, but there, just where her uncle had promised, were rags and tatters of black cloth – bits of sleeve or scarf or shawl – hooked onto the barbed wire. In all, maybe 20 pieces of funeral clothes left by people who were struggling to let go.

It wasn’t a holy place, she didn’t believe in any of that, but it was a place where people had come and waited and thought and felt. Something in the air held that. She listened, and the air sounded like a breath taken in and not yet released. She didn’t believe in ghosts either, but it did feel like here on top of the hill where there was no one – no walkers, no farmer, no chatter – she was, for this moment, not alone. She looked around. If there were others, then they remained unseen. Her spine gave a little shiver.

She hooked the hankie onto the wire, piercing a hole right next to the forget-me-not.

A breeze blew and it flapped in the wind like a flag.

She took in a big breath and then breathed it out. Like blowing away dust from a forgotten place.

She looked at all the other cloths – they were black, hers was a little white thing. A flag of surrender. No, a little metaphor of hope.

She felt blood running down her arm from where she’d hit her elbow; a jagged gash about an inch long. It seemed the first real thing she’d felt in years.

Her phone rang.

It was Gareth.

‘Lo.’

‘You all right?’

‘Yeah.’

‘The lunch thing, I’m not stalking you or anything, but I made a bit of a picnic, just two egg rolls and a big samosa from Tesco. I thought we could split it. And I brought a flask.’

Blood was dripping off her fingers, the white rag was waving, the rain was coming. And the offer of picnic lunch was an act of kindness that cut right into her and pushed other things, just for a second, to one side.

She turned away from the objects on the fence and started down the half-track. The buzzard called at her again and Awel shouted back ‘Hello Mister Buzzard’. She gave a little laugh and started to run, like a child, faster and faster down the hill, across the field, and perhaps to a better place.

Credit: Kevin Dyer

Kevin lives in Rhuthun. Before this he lived in Pentrellyncymer, before that Cardiff. He has a particular interest in how location and landscape shape our lives. He is Associate Artist for Farnham Maltings, Associate Writer for ATT and Lead Artist for Storm in the North Theatre. He was recently digital writer in residence for ‘Writing on the Wall’.

He works as a dramaturg and writing mentor, and has won or been shortlisted for many playwriting prizes. These include:

Winner: International Inspirational Playwright Award. Presented by Assitej International at their World Congress in Cape Town.

Winner: UK Theatre Awards. Best Play. ‘The Hobbit’, adapted by Kevin Dyer.

Winner: Writers’ Guild of GB. Best Play for Young Audiences, ‘The Monster Under the Bed’.

Twice winner, Olwen Wymark Award for supporting other writers.

He has just finished his first novel, ‘Marion’. It’s about a cow.

Through the From Now On project, Kevin received mentoring support and critical feedback from Durre Shahwar, Co-founder of Where I’m Coming From.